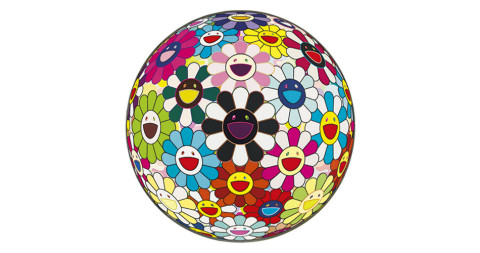

February 22, 2016Above, the face of Japanese artist Takashi Murakami is bedecked with his signature Pop motifs, including laughing flowers, in Murakami +, a 2011 digital photograph by Bruno Timmermans. Top: Murakami sits among his “Superflat Collection,” which is the focus of a new show at the Yokohama Museum of Art. Photo by Kentaro Hirao

Japanese Pop artist Takashi Murakami is one of the most compelling and prolific art impresarios working today. About 20 years ago, the progenitor of the Superflat movement set up a company with studios in both Tokyo and New York so that he could produce and promote his art and merchandise 24 hours a day while also marketing younger talents under his management. In the process, he became nearly as compulsive a collector as he is a creative entrepreneur. That is but one of the many revelations of the Yokohama Museum of Art’s new exhibition, “Takashi Murakami’s Superflat Collection — From Shōhaku and Rosanjin to Anselm Kiefer.” Running through April 3, it features more than a thousand objects that the art star has accumulated since he began collecting as a student.

Akiko Miki, the show’s curator, points out that Murakami has long been interested in the expressive potential of curation. “Murakami has often organized group shows or events concurrent with his major solo exhibitions,” Miki tells Introspective. “He launched the first incarnation of GEISAI — an influential biannual art fair-slash-happening he conceived to promote the work of fledgling Japanese artists — on the landmark occasion of his 2001 show at Tokyo’s Museum of Contemporary Art.” (It was his first major museum exhibition in his native land.)

Four years later, he organized “Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture,” at the Japan Society in New York, which New York Times critic Roberta Smith described as “psychoanalysis on a national scope in exhibition form,” and “the most daring, thought-provoking show yet seen” at that institution.

Murakami also collects the work of such Edo-period nonconformists as Soga Shōhaku, whose Teika, Jakuren, and Saigyō (above) fits in well with the Superflat aesthetic.

Miki says that Murakami asked her to collaborate on displaying his personal collection of art and ephemera when they were in the midst of preparing for his solo exhibition of new works at Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum (the show opened last October). Exploring the role of art and faith in the face of calamity, the show, called “The 500 Arhats,” was his response to the devastating Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami of 2011.

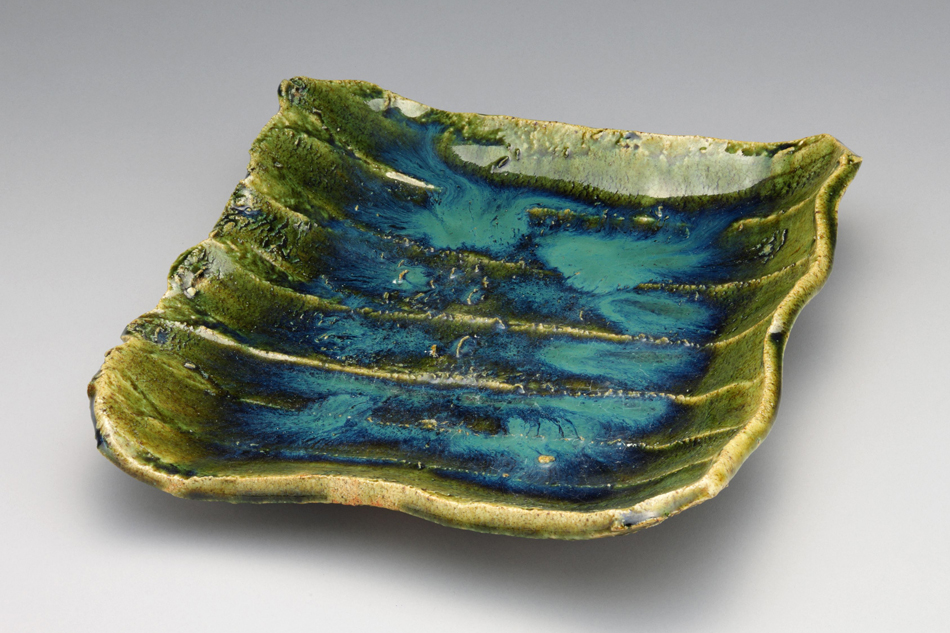

When Murakami first floated this idea, Miki must have shuddered at how personally revealing the exhibition might be. Although she knew that Murakami was an avid collector and was aware of some of the art he owned, she had no idea of the extent or details of his collecting, since he kept his trove in a warehouse on the outskirts of Tokyo. What she discovered, she says, was that his collection “included not only works of fine art but also ceramics, artifacts and antique furniture, as well as such Western and Asian ephemera as beer mugs and fantasy figures.” Her biggest surprise? His assortment of dust cloths.

As a curator, Miki was intrigued to see that the concept of Superflat was prevalent throughout the collection. (Murakami, it should be noted, has a Ph.D. in the traditional Japanese painting style of Nihonga, so he knows his stuff.) She explains that the term “Superflat” not only refers “to the formal aspects of Japanese art, such as the flatness of the picture plane and decorativeness, which is also found in manga and anime, but also extends to a view of art that rejects hierarchical divisions between different artistic genres or eras and frees artistic activities from definitional boundaries.”

Light My Fire, 2001, by Murakami’s contemporary Yoshitomo Nara. Photo © Yoshitomo Nara, courtesy of the artist

And so the dust cloths hold the same pride of place as installations by such art-world pranksters as Maurizio Cattelan and David Shrigley and pieces by Edo-period nonconformists like Shōhaku Soga and Hakuin Ekaku. Other works that offer insight into Murakami’s aesthetic ken include a 3-D-printed nude of the transgender poet and artist Juliana Huxtable by Frank Benson and a 2014 installation by Korean minimalist Lee Ufan. Perhaps, most surprising — and revealing — is Merkaba (2010), a glass vitrine containing an enormous ruin of a fuselage by Anselm Kiefer, Germany’s Sturm und Drang poet of the postwar. Apparently, Murakami saw the sculpture at a 2010 show at Gagosian Gallery, which also represents him, and when it didn’t sell, he bought it on an installment plan. In an interview with Art Newspaper, he cites Kiefer as “the symbol of my becoming an artist.”

With this exhibition running concurrently with “500 Arhats,” Murakami seems to be seeking to engage the public in a discussion about the nature of the art market and its role in assigning value. “One of the things the exhibition delves into,” says Miki, “is the question of what drives the human urge to collect or claim ownership of things. In that way, Murakami and his collection are lenses through which we can examine . . . the interweaving of art, politics and desire.”

In his Art Newspaper interview, Murakami confessed that he is still adding new purchases to the exhibition. “Collecting,” he declared, “is an illness. I wouldn’t recommend it.” Of course, many artists have said the same thing about love, and it hasn’t yet stopped humankind from loving or collecting or figuring out how entangled the two can become.