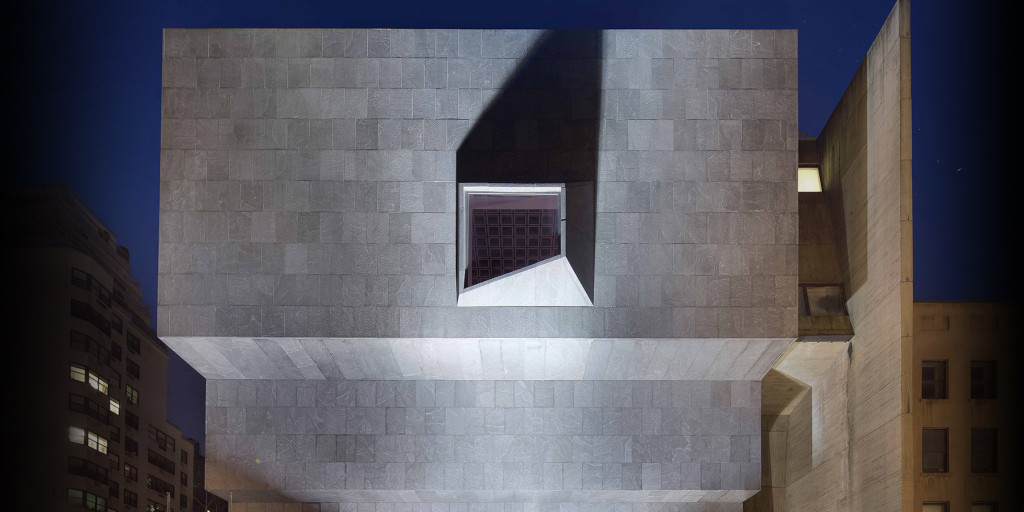

February 29, 2016Above: Crowds lined up across the bridge leading to Marcel Breuer‘s then-new Whitney Museum of American Art in Manhattan on September 27, 1966, the day after it opened to the public (photo by Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images). Top: On March 18, the Brutalist-style building, whose Cyclopean window is accentuated here, will reopen as the Met Breuer, under the stewardship of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (photo by Ed Lederman).

It is one of Manhattan’s most distinctive buildings — a 50-year-old concrete and granite Brutalist icon in the form of an upside-down ziggurat with a single Cyclops-eye window on its front facade, cheekily inserted among the brownstones of the Upper East Side. The only major architectural project in New York City by Marcel Breuer (1902–1981), a towering figure of 20th-century modernism, it served as the Whitney Museum of American Art until 2014, when that institution decamped for its new Renzo Piano–designed home downtown.

When the Breuer building at Madison Avenue and 75th Street reopens to the public on March 18, it will have a new tenant — none other than the Metropolitan Museum of Art, its neighbor just a few blocks to the north and west. (This will be the Met’s second outpost; it acquired the medieval, art-filled Cloisters, in upper Manhattan, in 1938.) The Met Breuer will debut with a slate of shows that signals an intent to seriously explore, in museum director Thomas Campbell’s words, “narrative resonances” between the Met’s traditional historic purview and the realms of global, contemporary and live arts. There’s the blockbuster “Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible,” surveying nearly 200 never-completed works, from the Renaissance to the present; the first-ever retrospective in the United States of Nasreen Mohamedi, a little-known Indian modernist; and continuous performances by visionary pianist Vijay Iyer in the lobby, under Breuer’s memorable ceiling of circular lights.

“We are burnishing and buffing the building, removing extraneous details and taking it back to 1965,” Campbell says. “It’s a stunning work of art in its own right.”

Breuer in a conference room of the Whitney Museum. Photo © Ezra Stoller/Esto

Breuer would no doubt be pleased. Born in Hungary at the turn of the last century, he was a Bauhaus-trained architect who became head of the furniture department at that seminal German design school. As the Nazis rose to power in the 1930s, Breuer and his mentor, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, emigrated to England and then to Boston, where they practiced architecture together. Breuer also taught at Harvard University from 1937 to ’46, spreading the gospel of international modernism to a generation of American architecture students.

He went on to design numerous modernist residences, mostly made of glass and stone, in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, New York’s Hudson Valley, Connecticut’s New Canaan and elsewhere. In the postwar years, however, he became known for his muscular Brutalist-style concrete buildings, like the much-admired 1958 UNESCO headquarters in Paris and the less-loved 1968 headquarters of the Department of Housing and Urban Development in Washington, D.C.

When Breuer conceived his iconoclastic building for the Whitney, “he thought the whole of the Upper East Side would become blanket high-rises and commerce,” says Beatrice Galilee, the Met’s associate curator of architecture and design, who came to the then-newly created post two years ago from London. “Part of his design was about sheltering art from all that.” To fend off the anticipated march of steel and glass up Madison Avenue, Breuer built an opaque wall of shuttered concrete to the south and an almost-medieval bridge from the sidewalk to the building’s lobby over a sunken garden — now planted with aspen trees — sparing the fenestration. The effect is of a serene cloister, set apart from the city outside.

“Breuer had such a skill for using materials and a meticulous approach that came from his years as furniture master at the Bauhaus.”

The five-story, 85,000-square-foot building is “a study in concrete,” Galilee says, pointing out planks bearing the marks of the wooden molds used to form them and thickly textured concrete walls, jackhammered in spots to reveal the dark aggregate within. “It was quite influential, in the sense that a museum didn’t have to be all-white cubes.” (The entire ensemble is encased in 1,500 granite slabs.)

Beyond a painstaking cleaning, subtle new signage and, in a concession to 21st-century tastes, a darker stain for the parquet gallery floors, nothing major is being done. “We really don’t need to change the space,” Galilee says. “Breuer had such a skill for using materials and a meticulous approach that came from his years as a furniture master at the Bauhaus.”

Indeed, most people are more familiar with Breuer’s early furniture designs than with his architecture. “Breuer’s influence as a furniture designer cannot be overstated,” says David Carter, of Chicago’s Pegboard Modern, which currently has a pair of bicycle-inspired Wassily chairs, designed by Breuer at the Bauhaus in 1925 and manufactured under license by Knoll in 1968. The first tubular-steel chair designed for residential use, it has a complex framework of exposed intersecting metal poles, with an angled leather seat and back.

“It’s a stunning work of art in its own right,” Met director Thomas Campbell says of the building. Photo by Ed Lederman

“Breuer’s experiments with steel tubing as a material for furniture making was groundbreaking,” says Andrew Duncanson, of Stockholm’s Modernity gallery, “and his mastery of plywood, simultaneous with the Nordic architects Alvar Aalto and Bruno Matthson, was revolutionary.” Breuer’s plywood Long chair, a rare example of which Modernity currently has on offer, suggests the flow of living tissue. It was designed for the British furniture company Isokon in the mid-1930s and is considered the pinnacle of the series.

In some ways, Breuer’s reputation as a furniture designer has been the victim of his overwhelming success. Who hasn’t sat in some version (authentic or otherwise) of his cantilevered Cesca chair, with its tubular chrome frame and caned seat and back? “Some of Breuer’s furniture designs have been so copied, it’s easy to take them for granted,” says Carter. “Then you encounter a genuine vintage example and are struck by how innovative and elegant it really is.”

Later this month, visitors to the Met Breuer will be struck in much the same way by the brilliance of Breuer in his later years — and on a much grander scale, too.